The results are impressive: The Michaela Community School in northwest London claims the highest rate of academic advancement in England. It’s particularly impressive given that Michaela’s students come from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The results are impressive: The Michaela Community School in northwest London claims the highest rate of academic advancement in England. It’s particularly impressive given that Michaela’s students come from disadvantaged backgrounds.

We’re so starved for good news about our schools – any good news – that a big part of me wanted to do a happy dance as I read about Michaela’s decade-long success story. And I wanted to cheer the other schools in the United Kingdom that are mirroring Michaela’s methods to improve their own results.

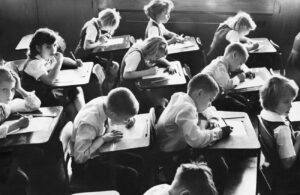

And yet. The more I learned about the details of Michaela’s approach, the greater my misgivings. The school climate just sounds … oppressive. Consider: Hallways are silent because students are not permitted to talk to each other. At lunchtime, students eat for 13 minutes (not 12 or 14) and must use that time to engage in conversation about mandated topics. The day is so regimented that the school relies on digital clocks because, as the principal, Katharine Birbalsingh, told the New York Times, “traditional clocks are not precise enough.” No wonder Ms. Birbalsingh feels confident describing herself as “Britain’s strictest headmistress” in her own social media profiles.

This is probably a good time to state that I’m not writing this to take potshots and Ms. Birbalsingh or her school. As much as we need good news about schools, we also need to stop wagging fingers at every decision or policy we don’t agree with. Tearing people down doesn’t solve anything.

So let me focus for a moment on the ways in which I agree with Ms. Birbalsingh’s approach. “How do those who come from poor backgrounds make a success of their lives? Well, they have to work harder,” she told the Times, adding that, “children crave discipline.” Rowland Speller, principal of a school that is borrowing Michaela’s methods, justifies the discipline by noting that a regulated environment is reassuring for students whose home lives are volatile. Personally, I’d replace the word discipline with structure in Ms. Birbalsingh’s quote, but otherwise I agree with where she and Mr. Speller are coming from.

And although many people seemingly find it to hard to believe (guests are asked not to “demonstrate disbelief to pupils when they say they like their school),” many students say they are happy at Michaela. Clearly, something is working.

The school’s defenders say that Michaela’s strict discipline is a response to progressive, child-centered approaches to education that were popularized in the 1970s and resulted in a behavioral crisis, reduced learning, and inhibited social mobility.

I agree that we are facing a behavioral crisis. But here’s where I disagree with Ms. Birbalsingh and her allies. I don’t believe that we have to choose between classroom chaos and martial law. And Ms. Birbalsingh’s approach is martial law: The zero-tolerance policy prompts detentions for infractions as minor (in my view) as forgetting a pencil case.

My perspective is that Ms. Bibalsingh has chosen an authoritarian style over an authoritative one. Sure, a “because I said so” authoritarian approach can yield positive results. But at what cost? The authoritarian approach denies students the opportunity to participate in developing and enforcing their own classroom rules. It doesn’t help them understand their own behavior. Worse, it positions teachers as enemy enforcers, not allies.

Experience has taught us that students (or any of us, for that matter) don’t respond well to an authoritarian environment. They typically rebel or withdraw. They often become more focused on avoiding a negative outcome (punishment) than on pursuing a positive one (learning something).

Critics of the Michaela’s methods have expressed other concerns that I share: punishment for minor offenses takes a psychological toll; looking to academic success as the only benchmark for success doesn’t develop autonomy or critical thinking skills.

I don’t see discipline as an either/or proposition: That we have either strict discipline or classroom chaos. The Time to Teach strategies have proven that it’s possible to have disciplined classrooms and to develop critical thinking skills and healthy emotional management skills.

Lucie Lakin is the principal of Carr Manor Community School in Leeds, a school that doesn’t use the zero-tolerance model. Ms. Lakin told the Times that before choosing any discipline model we should first answer a basic question: “Are you talking about the school’s results being successful, or are you trying to make successful adults?” she asked.

Personally, I’ll choose making successful adults every time. How about you?