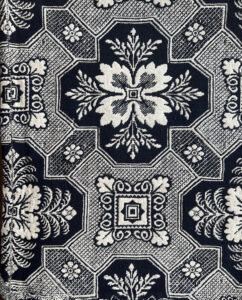

Whenever I went to stay with my grandparents – which was often – one of the first things I did was go to the linen closet to help myself to what I had always called The Blanket. Not only was it cozy warm, but it was beautiful: A Navy blue and white floral pattern with the reverse pattern on the underside. But what really made it special is that it was handmade by my great, great grandmother and she had woven the date she completed it – 1842 – into the corner.

Whenever I went to stay with my grandparents – which was often – one of the first things I did was go to the linen closet to help myself to what I had always called The Blanket. Not only was it cozy warm, but it was beautiful: A Navy blue and white floral pattern with the reverse pattern on the underside. But what really made it special is that it was handmade by my great, great grandmother and she had woven the date she completed it – 1842 – into the corner.

As I would drift off to sleep, I loved imagining all the generations before me who had fallen asleep under the same blanket. I loved considering all the skill, creativity and hours that had been invested in creating it. I wondered what had inspired the floral pattern. Was it a pattern my great, great grandmother had designed herself, or had she admired it somewhere and replicated it? Either way, I felt connected to the blanket. My great grandmother, who I was fortunate to know and remember, had slept under it as a child. So had my grandmother. And my mother. It was part of our family story.

I was convinced – and still am – that the blanket is perfect. But technically, it isn’t. At some point in its history, the blanket developed a hole. The hole is somewhere between the size of a nickel and a quarter. Given that the blanket is large enough to cover a modern queen-size bed, it’s not a large hole. But it is noticeable, because the hole was repaired with gold thread.

No one in the family knows when it was repaired, or who did the work. I’ve always assumed that my great, great grandmother herself did not repair it. The rest of her work is so precise that I can’t see her using gold thread to fix a hole in a sea of blue. No, someone else repaired the blanket. I’ll never know for sure, but when I put on my Hercule Poirot detective hat I conclude that whoever did the repair just saw a hole. Fixing the hole was more important than the integrity of the design.

And yet I love the random spot of gold. Years after I first started sleeping under the blanket, I learned about the Japanese practice known as kintsugi. It translates roughly as “golden repair,” and it’s a technique for repairing damaged artwork, such as ceramics or pottery. The technique involves mixing powdered precious metals (usually gold, but sometimes silver or platinum) with lacquer. The end result doesn’t disguise the flaw – it highlights it.

The thought behind kintsugi is profound. The idea is to turn the object’s imperfections into a part of its beauty and history. Kintsugi aligns with the Japanese aesthetic philosophy of wabi-sabi, which finds beauty in imperfection, impermanence and the incomplete. The flaws are seen as part of the object’s life story, adding to its character. Kintsugi also embodies a deeper philosophical message about resilience and transformation. It suggests that there is beauty in healing, which can make an object even more valuable.

I’m quite confident that any connection between the gold thread in the blanket and kintsugi is nothing more than coincidence. And yet. Although I couldn’t have articulated why, even as a child I thought the small spot of gold added to the blanket. It enlarged the story. When I did learn about kintsugi, I was especially moved that it honors resilience. It was that that I really sought to understand what the family had suffered in the Civil War, which devastated their corner of the Shenandoah Valley.

I’m not sure what it says about how my brain works that recently I’ve been thinking about all this – the blanket, kintsugi, the Civil War – as I’ve been reading about recent decisions to remove some books from libraries. All our individual stories, the nation’s story, the human story, are flawed. We are, at best, imperfect. Sometimes we are ruthless and cruel. But we are also resilient and we learn and we become better. We are a work in progress.

Personally, I don’t know how we can understand or appreciate that without knowing our whole story. To me, there will always be books in the library that are spots of gold thread: Conspicuous reminders of uncomfortable truths, but essential parts of our story.

Without them, we’re just left with holes.